Skin and Story: Tattoos and Identity

- tattoos

- identity

- inked skin

- Nineteenth Century

This is the first in a series of blogs to accompany the exhibition TATTOO: British Tattoo Art Revealed, at Torre Abbey. This series, like the exhibition, aims to challenge some of the longstanding preconceptions about the history and culture of tattooing and it asks along the way: What is distinctive about British tattooing? And, is there something distinctive about tattoos in the South West?

One of the most striking things about this exhibition is the way it challenges or modifies our view of tattooing as a distinctly foreign import, as traditionally a practice confined to sailors and military men, as largely an expression of rebellion against society (and thus mostly associated, at least in the early days of modern tattooing), with criminals, ‘freaks,’ and then outlaw bikers.

Now, some of these perceptions, as we will see in the coming weeks, have their foundations in fact, but tattoo culture has been, and continues to be, much more complicated. It has evolved in some unexpected and surprising ways. Over the next few weeks, as we explore the exhibition and think about the issues it raises, we will excavate some lesser known things about the history and culture of tattooing.

In this first article, we focus on Tattoos and Identity.

An Inked magazine column describes a study conducted by Dr Viren Swami, a London psychologist who conducted a number of studies aimed at identifying shared personality traits among tattooed people.

In a 2011 London study of people who were considering getting a first tattoo, he found that Individuals who decided to go ahead were ‘less conscientious,’ than those who did not, and were ‘more extroverted, more willing to engage in sexual relations in the absence of commitment, and had higher scores on sensation seeking, need for uniqueness, and distinctive appearance investment.’

But before we think these are significant differences between the tattooed and untattooed, Swami emphasised that most of these characteristics were ‘heightened but not extreme when compared to the majority of the population.’ In addition, he concluded that the tattooed population was ‘not restricted to any particular social class, gender, or ethnic group.’

In another 2012 study, Swami and colleagues at the University of Vienna surveyed 540 people, mostly Austrians, including 140 with an average of 2.7 tattoos. Their study found that compared with individuals without tattoos, inked people were more extroverted and experience-seeking, and the researchers concluded that ‘tattoos may now be an important means through which individuals can develop unique identities.’ 1

There are, of course, limits to these kinds of studies, and we could debate this.

What I’m interested in, though, is this desire to define, to identify, to categorise, to compare and contrast, and to group people. This is not new, and there have been many attempts to use the tattoo to define individual and collective identities.

Reading Inked Skin in the Nineteenth Century

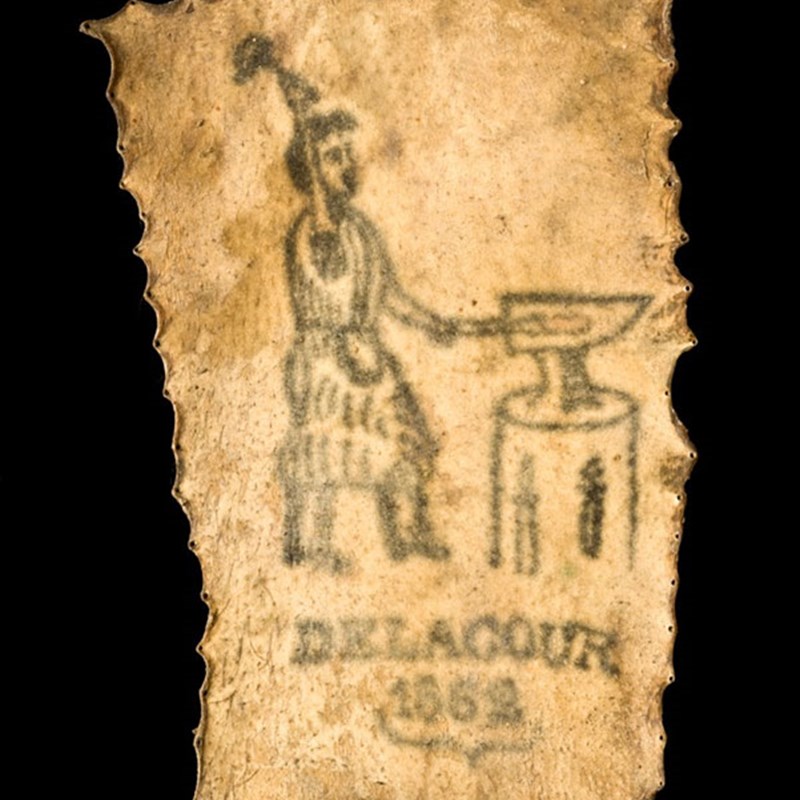

In the nineteenth century, tattoos were collected and preserved on skin as specimens. There are a number of collections of preserved tattooed skin specimens in museums across the world, from London to Tokyo. (On the collection of about 300 dry-preserved tattooed skins in the Wellcome Collection in London, see Gemma Angel’s blog at https://lifeand6months.com)

Why were these specimens collected? They were seen as a material, physical ‘key’ to the wearer. Tattoos were often markers of occupation and of relationships, and of the effects of institutionalisation.

Nineteenth-Century Tattoos, part of Henry Wellcome’s collection of 300 preserved tattooed skins, purchased in 1929, via one of his purchasing agents, Peter Johnston-Saint, from one Dr. ‘La Valette’, the ‘old osteologist’ at Rue Ecole de Medecine, Paris. @Wellcome Images, London.

Criminals, Deviants and their Tattoos

In addition, however, doctors, psychologists and early criminologists linked ink to the intangible qualities lurking inside the body: to criminal compulsions, secret desires and to psychological dysfunction, as well as personal among other things. Tattoos were indexes, they claimed, of a certain type of personal identity.

The early criminologist Cesare Lombroso used tattoos to flesh out ‘the criminal type’ - both male and female. In Lombroso’s hands, the tattoo became statistical.

In his book Criminal Man (1876), Lombroso argued that tattoos were forms of ‘stigmata’ - bodily signs of moral, biological and psychological inferiority. Their presence on the body indicated criminal tendencies: they were, he wrote, ‘the outward and visible signs of a mysterious and complicated process of degeneration, which in the case of the criminal evokes evil impulses that are largely of an atavistic origin.’ 2 By atavism Lombroso conjured the figure of Charles Darwin and his evolutionary theory: tattoos were an identifier of a savage strain that survived from the animalistic past, lurking within the psyche and biology of modern man and woman.

Tattoos were matched to certain types of body. They were part of a wider project to photography, measure, index, identify and statistically map the criminal body and face. If tattoos were stigmata, so too were things like irregularly shaped ears and fingers, sloping foreheads, large jaws, large and/or flattened noses.

In his essay ‘The Savage Origin of Tattooing’ which appeared in Popular Science Monthly in April 1869, Lombroso portrayed the tattoo as reflective of coarseness, commonness, of passivity, of irrationality; it was an emblem of regression, degeneration, and foreignness:

‘Tattooing is the true writing of savages, their first registry of civil condition...Nothing is more natural than to see a usage so widespread among savages and prehistoric peoples reappear in classes which, as the deep-sea bottoms retain the same temperature, have preserved the customs and superstitions of the primitive peoples, and who have, like them, violent passions, a blunted sensibility, a puerile vanity, long-standing habits of inaction, and very often nudity. There, indeed among savages are the principal models of this curious custom.’ 3

Revealingly, Lombroso wrote this in part to stem the latest ‘fashion amongst prominent society ladies’ of London—to get tattoos. So, then it seems inking was not the purview of the criminal classes only, as Lombroso would suggest. Underneath those bracelets on Lady Churchill (Winston’s mother) in the very genteel photography below, is a serpent tattoo wrapping around her wrist.

The negative representation of tattoos and the tattooed continued. In a 1968 article on ‘The Relationship of Tattoos to Personality Disorders,’ in The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science, Richard S. Post aimed:

‘to show that the presence of a tattoo, or tattoos, can serve to indicate the presence of a personality disorder which could lead to, or is characterised by, behaviour which deviates from contemporary social norms . . . [which] could be, but is not necessarily, manifested in the form of criminal behaviour.’ 4

Tattooing Today: Body Art and Personal Experience

It is quite remarkable, then, to see in this exhibition—and in everyday life—just how far tattooing has come, and the journey it has taken in spite of all of these attempts to contain it.

In the face of negative stereotyping it as a delinquent practice and to categorize those who wear them as criminals and outcasts, and despite the problematic diagnostic modes of sociological interpretation, tattooing have survived and flourished.

Inking has evolved into what Karen Leader describes as ‘a shared cultural experience, rather than as a symptom, or a fad.’ The tattoo, she adds, has become ‘a repository of memories and a site of affirmations, but also a significant form of creative, embodied self-expression, beyond temporary fashion.’ 5

I think this is right, for as ‘Torbay Tattoo Tales’ reveals, these days, people most often describe their tattoos as an expression of their own experiences: of tragedies, of illnesses, of serious challenges faced and overcome. They very often symbolize loved ones lost (and found!); they are, too, about the activities, events and occupations we feel passionately about.

In one of the Torbay Tattoo Tales, for instance, Ross Ansell-Baker describes how his full back piece—which includes a skull and peonies—represents the reality of living with cystic fibrosis and how the condition has, in very measurable ways, shaped his life (and life expectancy). His is just one of many, many stories that are being gathered to create a new archive created (one very unlike the preserved skins at the Wellcome Collection!).

- InkedMag.com - What does your tattoo say about you/ | ↩

- C. Lombroso & G. Lombroso, Criminal Man (New York: G. Putnam & Sons, 1911), p. 24. | ↩

- Popular_Science_Monthly: Volume_48 April_1896 - The_Savage_Origin_of_Tattooing | ↩

- Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology: Volume 59 | Issue 4 - Relationship of Tattoos to Personality Disorders - Richard S. Post | ↩

- K. Leader, ‘“On the book of my body”: Women, Power, and “Tattoo Culture,”’ Feminist Formations (28: 3) Winter 2016, pp. 174–195, p. 174. | ↩